Boxing is crooked. Boxing is fixed. Boxing is a cesspool for the lowest form of human traffickers, those who extract money from athletes who put their very physical health and future on the line for our entertainment.

But it is also the most honest form of sport. A fighter is worth exactly what they sign for. Unlike basketball, football, or baseball there is no salary cap or luxury tax to limit his share of the market. Though wrong decisions are epidemic, the fighters know who won, and so do the fans. The belts are comedies of political favoritism and network pressure, but their very debasement means that we do not even have to pretend they exert meaning. Boxers are entertainers, they are the most aggressive form of capitalists, and as such I find it difficult to ever quibble with their matchmaking decisions. If they choose to go for the big money over fights that will build legacy and respect that is their prerogative.

So it is not without some self-conflict that I admit my deep despair over the upcoming mega fight between Oscar de la Hoya and Manny Pacquiao. When initial reports claimed that Pacquiao had balked over the 30% share of the fight’s revenue I was relieved, despite the knowledge that he had declined the largest windfall of his brief but spectacular career. Since he inevitably signed on for the fight my dissapointment has only grown.

It is not that De La Hoya is a bad man, and he has certainly proven himself to be an elite fighter over the course of his career. But at this point he has moved past the point of relevance. He is like Robert Deniro, or Jack Nicholson, someone still capable of giving a fine performance, but for whom there are no longer any stakes, where the embarrassment of a flop or the accolades of success don’t really reflect upon their careers.

And again, there is really nothing wrong with this in a global sense. I don’t think a fighter should be forced to retire unless absolutely medically necessary. Even a somewhat sad case like the final chapters of the heroic Holyfield’s career don’t bother me, as he plies his trade in the equivalent of the heavyweight minor leagues, taking fights against marginal Euros and no-hopers there is no pretense of meaning or jeopardy.

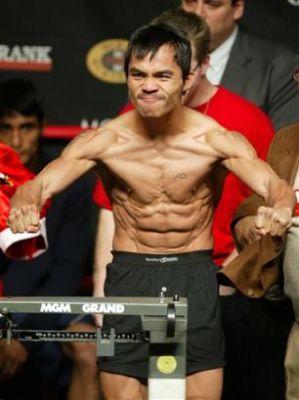

No, the problem comes when one of these vestiges of the elite thrust themselves back onto the main stage. Manny Pacquiao is now the top pound for pound fighter in the world, he has plunged himself through five divisions and the Mexican trio of Barrera, Morales, and Marquez with shocking violence and willpower. He is at the prime of his career, a fighting machine whose craft has finally caught up to his physical gifts. There is virtually nothing that it is not possible to imagine him doing.

It hurts to see him, at this point, his absolute apex, taking a freak fight, a toughman competition. Pacquiao, who only moved up from 130 pounds this year, will now be taking on a genuine 154-pound fighter. It is not merely the weight difference that is so daunting, weight is one thing, but the human frame is something else. Pacquiao and De La Hoya are not only in different weight classes, but truly in different zones of human body type. Their fist size, chest size, calves, are simply not comparable.

It reminds me of nothing so much as the early days of mixed martial arts, when they would match fighters for the freakish disparity of their bodies just to see what the hell would happen. Like a living test of a drunken barroom debate between friends. Who would win, Gandalf or Spiderman? But in those MMA events there was the element of the unknown, the integration of different forms of combat and skill level. As that sport has matured it has moved away from that macabre roman excess of violence and cruelty.

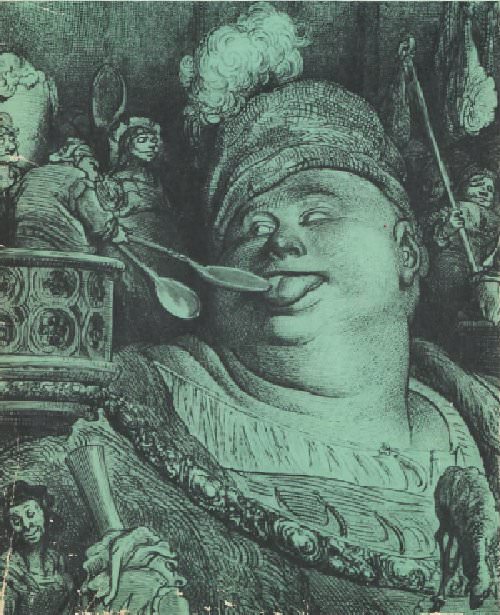

In this fight we have the worst of that instinct without much of the mitigating element of uncertainty. While de La Hoya has clearly deteriorated he is still a genuine fighter. I fully expect him to batter a noble Pacquiao around the ring, pushing him back and damaging him even when landing on the Philipino’s gloves until his corner is forced to spare him. Oscar will get his career-capping win, a sort of valediction for all he has done for the sport, but I will find it empty and sad. A win over relics like Vargas or Trinidad, while lacking any pretension of combat at the highest level, would at least have the weight of a match between equals. Oscar has stood astride the sport like a money printing colossus, but he will exit as a mere pile of excess bills.

And though this is Pacquiao’s prerogative, and his blood will be repaid with gold, it will be an empty feeling for all who watch. Even if Pacquiao is somehow able to do the unthinkable and actually win, my only reaction will be to marvel at how thoroughly Oscar’s gifts have faded to allow this to happen.

So what are we left with? A freak show, an interspecies fight, a paralyzed rhinoceros versus a jackal, who will win? It really doesn’t matter. Boxing is capitalism masquerading as sport, it always has been. When the two intersect as with Pacquiao’s last fight with Marquez, the results are both terrible and beautiful to behold. When they don’t we’re left with, this.

And yet… what does it say about me? Despite it all, I won’t be able to keep from watching.