1st round

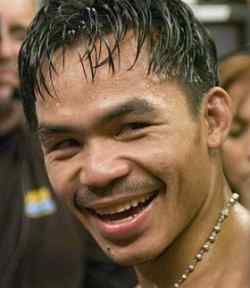

3:00-2:45: First thing we see is the size. Pacquiao may be smaller in the upper body, but he doesn’t seem disadvantaged otherwise. Next, Hatton’s clumsy footwork as opposed to Manny’s superfast darting balance. Against a normal fighter Hatton is faster and finds it relatively easy to close distance, in the first few seconds one can already see that’s not so.

2:30 The first landed blow is a sneaky right hook. Hatton comes forward with a tepid jab, looking to apply pressure, but Manny’s timing and precision shows immediately. We could almost stop here, as this first blow is basically the story of the fight. Hatton and Mayweather Sr. knew this punch was coming, had made fun of it on 24/7, but there was nothing he could do about it. If you look at 5:34 they talk about the move, prepare for it, but were instantly unable to respond. There has been a lot of revisionist history since the fight, blaming Hatton for leaving himself unprotected as he lunged in, but it’s the story of his career. Against most fighters he is fast enough to close the distance, against Pacquiao he was crushed every time. It's not that he didn't do this right, or he made that mistake, it's that Ricky Hatton just isn't as good at boxing as Manny Pacquiao.

2:10 After a few seconds of trying to mug Pacquiao on the inside, the fighters gain separation. Hatton is again forced to wade through Pacquiao’s punching zone and eats another solid right hook. A good fighter will be able to time shots like this a few times a fight. Lazcano landed a good one on Hatton in their fight. Malignaggi landed a couple. Pacquiao landed two in the first fifty seconds. Not with full power, but with incredible accuracy.

1:55 Here we see where Hatton is really doomed. He had just managed to slip the Pacquiao right for the first time, and at center ring throws his first earnest right at distance, but Pacquiao easily slips the punch and lands his first left hand. I think Hatton felt okay, as though he could eat the right, but that first left was thrown with force. The difference in speed, accuracy, and class is already clear. Hatton is a fast fighter, but he looks in poor shape already. He can’t close the distance safely, and at range his inferior handspeed and amateurish form gives him no chance.

1:46 Hatton manages to slip a left, but Pacquiao again lands the right hook at half speed and ducks away.

1:30 Pacquiao lands another right hook, and this one he has thrown for keeps. It is a perfect shot, comes from underneath, and Hatton goes stiff legged. Lampley misses it, calling a Hatton shot, but you can hear the sound of the impact. When watching it live I was already jumping up and down screaming. I truly felt the fight was over. Hatton has a very particular way of looking hurt. He stands upright and lurches with stiff, tin-man movements. Floyd had him this way multiple time before he put him down, Manny is not so merciful.

1:00 Again we see Hatton’s problem. Taking some time to regather himself he waits at distance, throwing a few jabs and exhibiting his version of “boxing.” This is what Teddy Atlas claims he should have done from the beginning, but it was really no sort of option. Manny easily manages to slip everything that Hatton throws at distance and lands two straight lefts before Hatton can even manage to raise his hands. In the David Diaz fight we saw much the same predicament, but while Diaz was slower, he managed to last with his high guard. Though marginally quicker, Hatton could in no way slip the straight left at distance. Floyd managed to nail him with dozens of his equivalent straight rights, but he didn’t throw with the same conviction and power that Manny did.

:56 The knockdown. Pacquiao throws the same right hook he had landed three times before, but Hatton, already buzzed from the previous straight lefts crumples to the floor. It’s a beautiful rhythm shot, perfectly balanced and thrown while dodging the counter. Again, people claim that Hatton did something wrong, which is true, but ultimately meaningless. This is the way he fights. It is flawed, but works against even very good fighters. Only a special few have the ability to take advantage of it. Tszyu, Castillo, Urango, Collazo, Malignaggi; they could all see the opening, and they could even find it occasionally, but not the way Pacquiao did. Floyd Mayweather waited the whole fight for the left hook; in fact he landed the exact blow in the exact spot in the ring in the 8th round of his fight against Hatton, two rounds before he achieved the knockdown. He had what it takes to execute. The flaw is much easier to see when someone with speed, force, and accuracy is able to lay it bare.

:26 Hatton tries to regain his composure, but there is nowhere for him to go. He can’t risk taking the lunge to get inside, and at distance Pac’s handspeed is almost comical. Hatton careens into the ropes, a look of pure haplessness on his face.

:08 Pacquiao scores the second knockdown on a straight left that connects through the glove to Hatton’s face. The only question after the first knockdown was if he could last the round, and he does an admirable job of taking a few punches, slipping a few, and is ultimately fortunate he goes down here. If he had managed to stay up a few more seconds Pac likely would have scored the killing blow. As the bell rings he tries for one more right hook but it comes up short.

Round 2:

2:37 Hatton comes out aggressively and Pacquiao responds in kind. He seems to be pressing a little bit. At 2:37 he loads up on a huge left that overshoots the target and opens himself to a ragged counter shot by Hatton. He wanted to end it with this shot but started from a little too far away. This is the same shot that he uses later to finish the fight. He threw it with full force, but mistimed it slightly.

2:31 Pac throws a 1-2, the jab followed by the straight left. This is his money combination, the one that he used to wipe out Barrera and batter Marquez. It lands flush on Hatton’s nose. It’s the first time in the fight he leads with it, and it’s still as effective as ever.

1:45 Pacquiao throws a hard and brutal combination, a left uppercut beneath the ribcage and then a straight left to the face that partially lands. Hatton almost seemed as if he was getting back into the fight, but the way he immediately drops his right hand to cover up his side shows that the shot hurt him. Manny’s body punching has gotten much better over the years. Though he didn’t land many here, this one was a good one.

1:03 This is an important moment. Pacquiao again throws that supercharged overhand left, and this time he gets even closer. Manny throws it with full power and it lands on Hatton’s upper chest. It is the exact same sequence as the final blow. Hatton lunges with a weak jab to close the distance and Pacquiao slings it like a baseball pitch, just a few inches too low. You can hear the loud smack as Manny’s fist hits the collarbone. The first one at the beginning of the round missed by a good distance, this one was closer, it’s like he’s honing in, timing the target. One gets the feeling he could have more easily continued landing the right hook, but he knows there is little danger, and the more powerful left will end the show.

:33 Manny throws another left to the body, left to the head combination that badly wobbles Hatton. He is throwing with full power, no fear. He seems to want to end it in one shot, not the lighter, quicker combination punching he used to force the stoppage against De La Hoya.

:08 The knockout. Not much description needed. It was the same moment as 1:03. Hatton tries to jab his way in, in fact does land the jab, but he can’t close the distance and Manny connects with full power. Hatton drops his right hand, a silly mistake, but again, one that he always makes. Manny seemed to use those two earlier misses as measuring shots, coming closer and closer before he finally timed it right. This was no lucky shot. It was thrown with full force and bad intentions. You can hear Manny grunt as he throws it, the only time he did so the whole fight. It’s an amazing shot, the kind one dreams about.

People view Pacquiao as a kind of naïf, but nothing about this performance was thoughtless, he enacted a game plan with brutal and scientific efficiency. It reminded me of the Floyd Mayweather fight with Phillip Ndou. In that match Roger Mayweather told Floyd on the ringwalk that Ndou was open to the pull-counter, meaning a drawing back to avoid the jab followed by a counter right hand. Mayweather proceeded to execute the move with frightening precision. It’s one thing to see the flaw, to know the opening, it’s quite another to be able to make it flesh.

What does this tell us about future fights? There will obviously be time for this later, but in my mind Manny has two potential opponents. If Cotto beats Clottey next month the fight is possible, as they are both represented by Arum. Cotto was the one big welter I always thought Manny could beat, because he’s not huge, and he’s somewhat fragile. While we can save a closer analysis for this later, take a look at what happened the last time Cotto fought a left handed 140 pounder. This is poor quality, but check out the punch that lands at the 4:55 mark.

Yes, Cotto has clearly improved, but that punch sure looks familiar.

And the other fight, obviously, is Floyd Money Mayweather Jr. It’s almost too big to talk about yet, like cancer or all you can eat bananas. A year ago I wouldn’t have believed it, but who’s to say Pacquiao couldn’t do it. Look at this.

And this, at 1:05.

Another blatantly unfair video. I’m picking out a couple of moments over the course of a career, incidental contacts in rounds that Floyd probably didn’t even lose. I could find dozens where Manny was similarly vulnerable. And yet, a man that can execute with such precision… who’s to say it’s not possible? All it takes is a fist, in motion, at a specific point and time in a specific spot, and you have… word made flesh.